Windows named pipes, being one of many available mechanisms for inter-component / inter-process communications, is interesting from a security perspective. While hunting for vulnerabilities in various bits of software, I often see the pattern of a privileged process that exposes a named pipe such that a client process can interact with it. More often than not, you’ll eventually be curious enough to want to snoop on the data that is transferred over this named pipe. At this stage you’ll Google “Windows Named Pipe Proxy”, find some results and away you go. My hope is that pipetap is another one of these results you’ll find that can help with your Windows named pipe reverse engineering journey. You can find it here: https://github.com/sensepost/pipetap

prior art

There are many approaches and existing tools to reverse engineer Windows named pipes. For me, the ultimate and most powerful approach will always be a Frida script. Hook the ReadFile / WriteFile (and variants) Windows APIs, and you have everything you need to both read and manipulate named pipe traffic. In fact, many tools that exist today leverage Frida:

There are also some more specialised tools that focus on specific aspects of Windows named pipes:

- https://github.com/cyberark/PipeViewer

- https://github.com/grayed/PipeExplorer

- https://github.com/gabriel-sztejnworcel/pipe-intercept

All of these tools (and many more I have not yet mentioned) are honestly great and can get you far, but I’ve often found myself searching for a more comprehensive and focussed approach. To that end, I set out to try and write something for me which may be useful to others too.

the components of pipetap

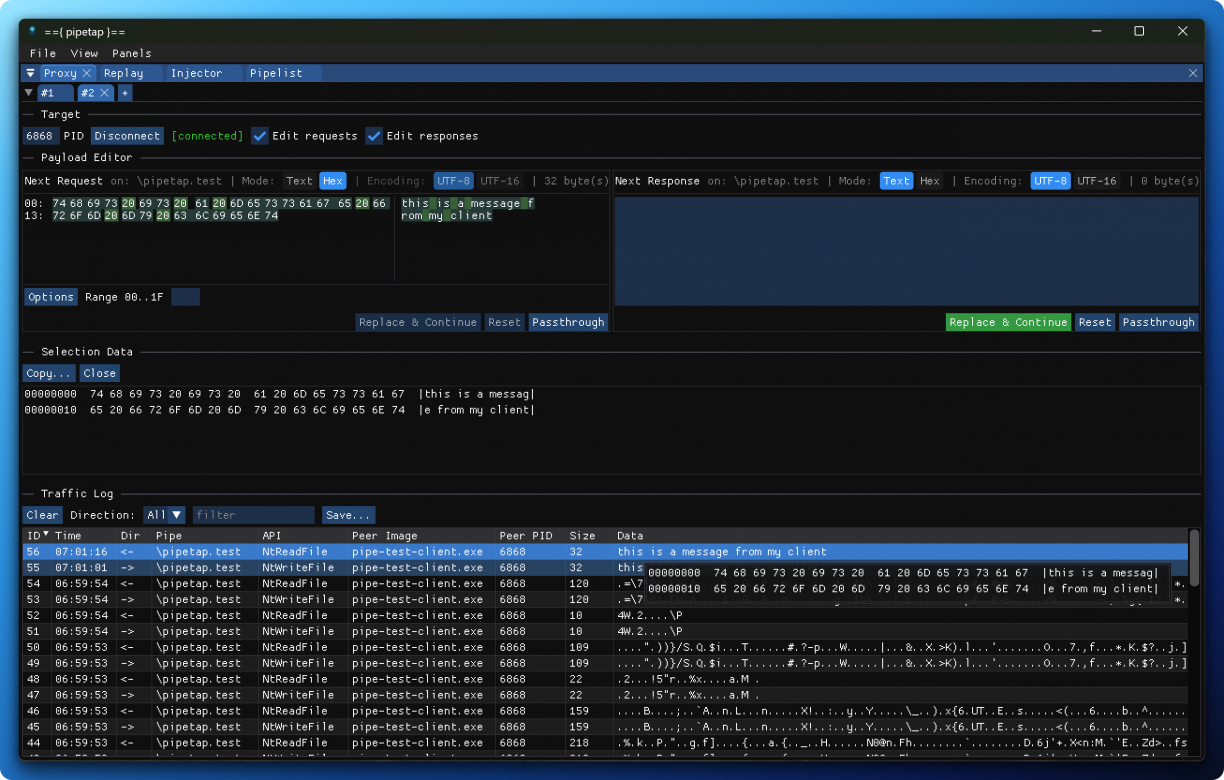

In its most basic form, pipetap is a Windows named pipe proxy. That is, it lets you intercept and change traffic that is sent and received over a Windows named pipe. It can do this because of a support DLL that should be injected into a remote process which in itself exposes a control channel (also over a named pipe, haha!) that the GUI you will use uses to drive the injected DLL.

The injected support DLL hooks Windows named pipe related APIs, and communicates to a connected GUI, firing events as they are occurring in the process. While you might expect Frida for the hooking here, I decided to go for the Microsoft Detours library given its small footprint and fairly simple API. In fact, the hooking code is less than 500 LOC, which includes all of the convenience helpers and more!

As for the GUI, this uses the amazing ImGUI library. It feels snappy as heck, and honestly a joy to write interfaces with. If you’ve used Burp Suite before, the interface should feel familiar.

pipetap features

Like I’ve mentioned, pipetap aims to be a proxy (which is really its primary feature), but it can do a lot more.

There is a support DLL injection helper. This DLL is key to the features of the GUI, so having an easy way to inject DLLs seemed necessary. The technique used is by no means stealthy, by design.

The GUI client lets you connect to multiple targets, meaning you can inject the support DLL into multiple targets too. This is quite handy when exploring multi process targets. I’ve seen some software that will juggle between 2/3 processes and various named pipes. This can be a lot to wrap your head around and one of the reasons pipetap works the way it does.

The proxy lets you export traffic in a JSON formatted document for further processing elsewhere if you need.

There is a pipelist feature that lets you enumerate available Windows named pipe servers (along with ACLs and more when enumerating in aggressive mode). Right-clicking entries lets you send parts to the appropriate tools.

It’s a pipe client in itself, meaning it can take an arbitrary named pipe name and try and connect to it. With a message composer that lets you build up string (utf8/utf16) or hex payloads, you can experiment with pipe servers. You can also import payloads generated elsewhere into the composer!

The pipe client also has a “remote client” feature. To understand this, you need to know that by default, if you connect the named pipe client, the source process making the named pipe connection will be the pipetap GUI. In the remote client case, connections come out of another process (i.e., not the GUI). To achieve this you need to start by injecting the support DLL into a remote process. Then you connect to your desired named pipe using the named pipe client by also specifying the PID of the injected process. In this configuration, the pipetap GUI will use the support DLL to initiate the named pipe connection instead of the GUI itself. This means that the named pipe server receiving the connection will think the other process initiated the client connection and not the pipetap GUI. This remote client feature has been particularly useful in cases where some hardened named pipe servers do what I’m just calling “calling PID validation”. That is, the server asks for the PID of the connecting process and does some security checks (i.e., code signature validation of the backing PE, etc.).

Speaking of named pipe clients, the support DLL also has a TCP to named pipe proxy. It is not always convenient to use a GUI to interrogate an unknown named pipe server. To that end, once injected, the support DLL will open a TCP port that can be used to programatically (and remotely) interface with a local named pipe. I added a small Python SDK to demonstrate how to connect to this server and use it here. You can get the python client with pip install pipetap then import pipetap in your project. I’ve used this with some virtual machine snapshot restoring logic and a nasty bash script before to fuzz a named pipe. :)

gotchas

I think the most obvious thing to keep in mind when using something like pipetap is that you will be messing with processes / state machines / connections in ways that were obviously not intended. Windows named pipes are fast, like really fast, and almost no software caters for latency or any form of delay. So, you might find yourself in a situation where you deadlock your target, or it slows down to a crawl thanks to the instrumentation. There is no one easy answer to all of these beyond, “it depends”. Good luck.

There are also some named pipe implementations that are not entirely complete in pipetap. Asynchronous named pipe communications still need a bit of work, but you should at least be able to see its usage.

wrap up

There are many options to investigate Windows named pipe traffic. Hopefully pipetap is another tool in the arsenal that can help make that a better experience.